By Kailan Manandic

It’s easy to take a balanced ecosystem for granted in the modern world. Sunlight fills any room at the flick of a switch, rivers run clean out of the faucet, and lightning hums behind every wall.

But cutting-edge conveniences come with significant complications, especially as more people tend to disregard the natural world that many communities rely on for recreation, biodiversity, and their own well-being.

“Our way of life that ties us to the land is what we describe as a relationship, which is a broader thing than what you understand as your relationship with your family,” says Nez Perce Tribe Cultural Resource Program Director Nakia Williamson. “Ours extends to the land and to the resources itself, and that's the core of our identity.”

The Little Salmon River is a vital watershed in Central Idaho that supports a varied ecosystem—providing critical habitat for a wide range of fish and wildlife species—and is deeply intertwined with the local culture. Over the years, however, the river has faced a range of challenges, including habitat degradation, overfishing, and water pollution.

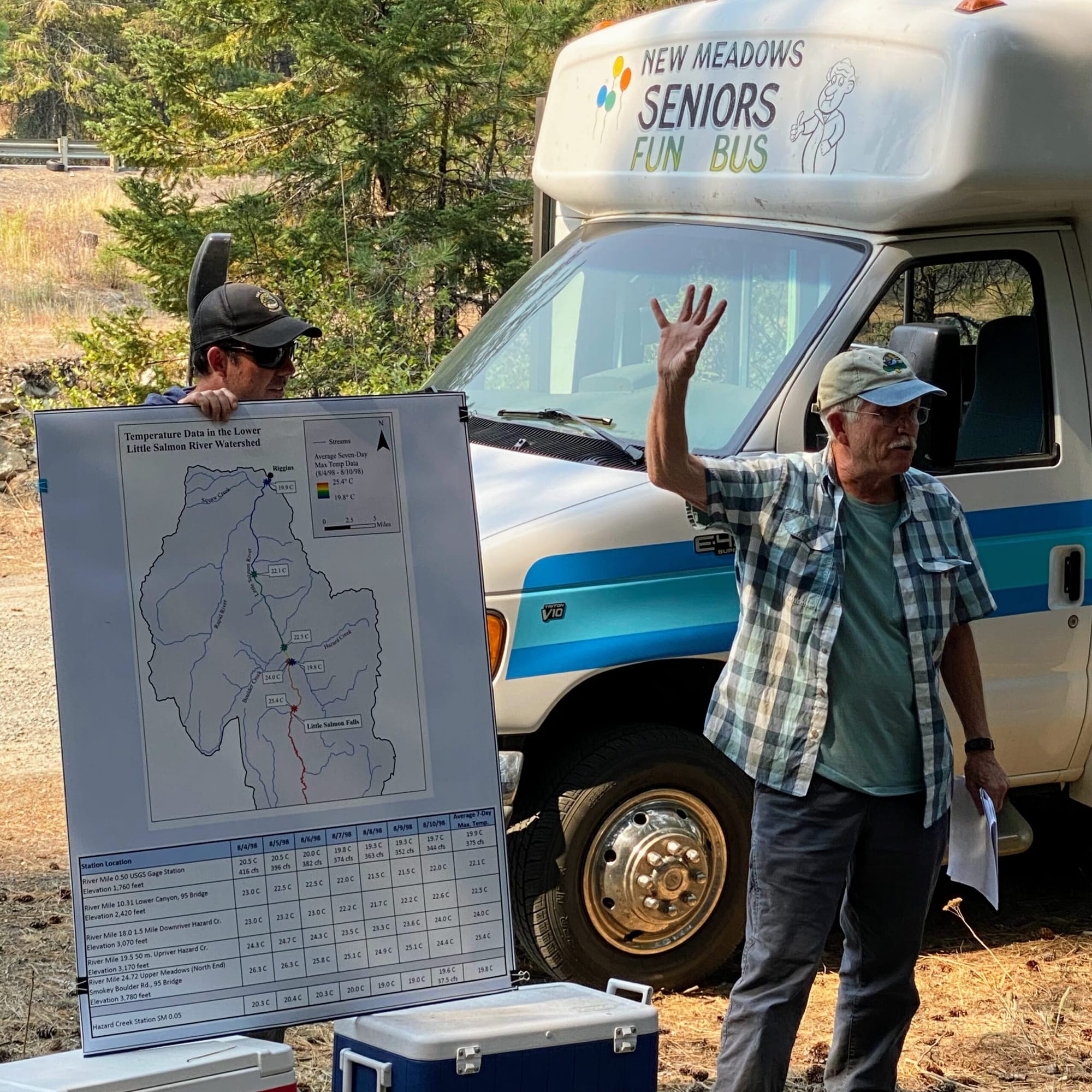

“In the Little Salmon, there are some impairments that are implicated by sediment, by bacteria, and by temperature,” says Kiana Ziola, water quality analyst for the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

To establish a foundation from which to assess and better address these issues, the Nez Perce Tribe Watershed Division formed the Little Salmon River Watershed Collaborative (LSRWC), an effort to restore the health of the river, protect it for future generations, and ensure everyone has a say in how their water will be managed.

The LSRWC, with funding from a Bureau of Reclamation grant, held regular meetings over two years, discussed the perspectives of various stakeholders, took action on the ground to improve the watershed, and consolidated everything they learned in an interactive website. The collaborative recently published its findings at the end of the funding cycle.

“In short, the goal was to come together and spend the two years learning more about the Little Salmon River Watershed,” says Gary Thompson, the collaborative facilitator. “We heard from people who live in the area, who work in the area, and who care about this watershed, and then created a list of priorities that the whole collaborative can support.”

The collaborative recognizes that effective conservation efforts require the involvement and support of the community. To facilitate engagement, the collaborative has developed a range of resources for stakeholders at littlesalmonriverwatershedcollaborative.com. Here, the collaborative highlights previous conservation efforts through an interactive story map, outlines the entire watershed and its various internal ownership boundaries, and provides technical assistance to landowners, helping them to develop conservation plans and access funding and resources to implement conservation practices.

“From what I saw, they put a great deal of effort into trying to bring everybody to the table—they had a lot of really great involvement from a diverse audience,” Ziola says. “Along the way, it provided opportunities for agency folks like myself to bring in what we're doing or what we've done in the past to help educate along the way.”

The Stakes

Protecting the health of the river is not only crucial for the ecosystem but also for the cultural identity of the community. The river is deeply connected to the cultural heritage of the Nez Perce Tribe, who have fished in the river for thousands of years

“We were part of those natural processes via our traditional gathering practices in which we're not only taking resources off the land, but we're actually engaged in the process and ecology,” Williamson says. “That's a kind of concept that's hard to kind of illustrate to people I think outside of our culture.”

The Tribe has recognized a significant reduction of fisheries resources and aquatic ecosystem degradation that has occurred over the past century. Because of this, the Tribe has developed a Department of Fisheries Resources Management (DFRM) program and Watershed Division to restore and protect these resources.

The vision of the Tribe’s DFRM Watershed Division is a watershed in which rivers and streams, the lifeblood in the veins of Nez Perce Country, and the ecosystems they support are healthy and valued. They envision a world in which the blood of life is treated with the utmost respect by all, and land-management activities ensure a sustainable balance with healthy ecosystems.

“So, the protection of these things is really important to us, of course,” Williamson says. “Water is the elemental basis for all life, and when we have our meals, we start by drinking water as kind of a sacrament, recognizing water is first and foremost.”

The Little Salmon River watershed encompasses about 370,000 acres located in the Columbia River Basin and totals approximately 370,000 acres. An area this large goes far beyond any one entity’s jurisdiction, though it does fall entirely within the Tribe’s Ceded Territory Boundary. This land was ceded to the United States, but the Tribe retained rights to it as stated in the Tribes Treaty of 1855.

“The Exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams where running through or bordering said reservation is further secured to said Indians,” the treaty says. “As also the right of taking fish at usual and accustomed places in common with citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary buildings for curing, together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horse and cattle upon open and unclaimed land.”

The LSRWC was successful in bringing together a wide range of stakeholders, including federal, state, and local agencies, non-profit organizations, private landowners, and, most importantly, Tribe representatives. The collaborative also included people involved with the agricultural industry, as well as recreational users of the river. By bringing together such a diverse group of stakeholders, the collaborative developed comprehensive solutions that address the needs of all parties involved.

“The idea is that, with collaboratives in general, we don't necessarily have to agree on everything—whatever we do agree upon will have more strength in the long term,” Thompson says. “I've always said that what makes collaboratives work is progress and purpose. Our purpose is to come up with ‘X’ number of recommendations that we can all support, and so the more diverse the voices are that support certain recommendations, the more legs they have so something can actually happen.”

Approximately 4 percent of the watershed is owned and managed by the state, 31 percent is privately owned, and 65 percent is publicly owned—the Bureau of Land Management manages about 4 percent while the United States Forest Service manages the remaining 61 percent. State and BLM land is located intermittently along the river itself, with private landowners owning a majority of the riverside property.

The Wallowa-Whitman National Forest (NF) and Nez Perce-Clearwater NF manage the northwest portion of the Little Salmon River watershed, and the Payette NF manages the west-central and east-central regions of the watershed as well as the southwest corner.

Downstream Effects

With so many owners and boundaries, the collaborative had to account for numerous voices who each have their own emotional and financial attachment to the land.

“It’s a lot to coordinate,” says Wes Keller, a project leader with the Nez Perce Tribe Watershed Division who spearheaded the grant application and the collaborative itself. “We started looking for grants and we found the Bureau of Reclamation water smart grant. We were pretty excited by this because it funds exactly what we're doing here.”

While the funding has run dry, the collaborative’s efforts will live on to help guide the future of the watershed’s restoration.

As the DEQ assesses the watershed, they take into account the needs of the people who rely on the land. They collect and analyze samples from the river and undergo intensive field processes to understand bank stability and the physical characteristics of the vegetation that's present. Looking at these indicators and the LSRWC findings, the DEQ allocates resources and creates projects to ensure the Little Salmon River watershed will thrive for generations to come.

“The resource that they created as kind of the end project—the website that they have—is an awesome resource that we'll be using,” Ziola says. “They've done a great job in incorporating the resources that DEQ has to share on that platform. It's kind of like a great one-stop-shop platform that they've created and put a great deal of effort into.”